My mold sabbatical to Death Valley was the beginning of my experience with extreme mold avoidance, and even now, if I get a nasty series of exposures, time in the wilderness can be critical tool to give my body a break and allow it to recover. Our van, Gracie makes that far, far easier. (John came up with that wonderful name, because she's gray and because she's a bit of grace in our lives. Maxine, our Vanagon who stars in the book, suffered a sad death.)

While that necessity can be highly inconvenient, it's hard to complain about spending time in a place like this!

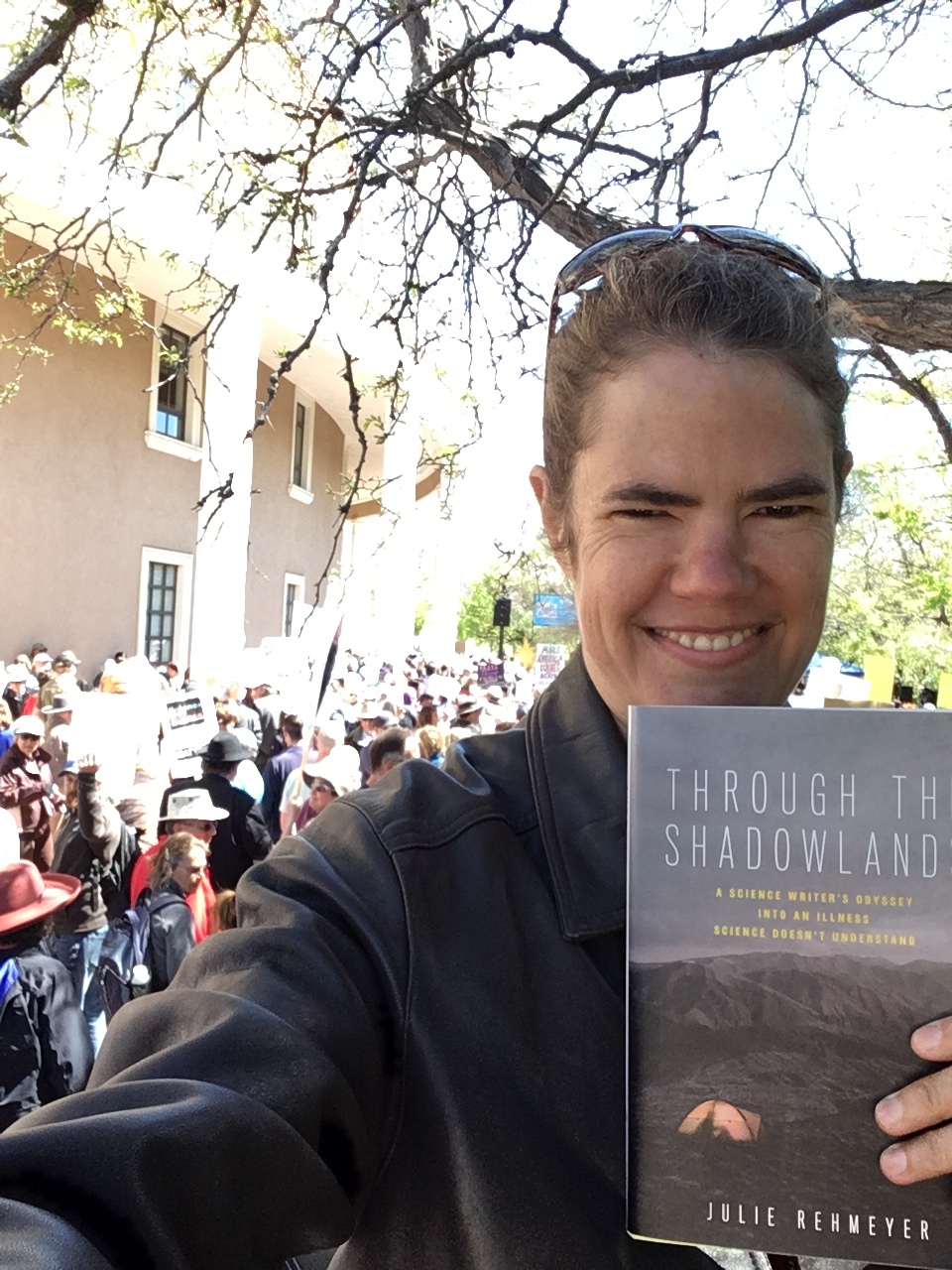

In writing Through the Shadowlands, my goal was not to evangelize for extreme mold avoidance. It was incredibly helpful to me, and it’s incredibly helpful for some other people, but it’s only one tool among many. And frankly, in many ways, it sucks – it’s expensive, it requires an extraordinary level of effort, and it can be unbelievably stressful and scary. I hope the time comes when no one has to do this because we have far better treatment options.

But that time hasn’t come yet for many of us, and I regularly hear from people who are inspired by my book to try a mold sabbatical. So I wanted to offer some practical advice, in case you’re thinking of giving it a shot.

1. Think hard about whether you really want to do this

Honestly, it worries me that people will read my book and assume that they'll have the same experience I did if they head for the desert for a couple of weeks. Looking around at other mold avoiders, people seem to have a really wide range of results — including getting stuck in severe hypersensitivity and being unable to live indoors. So please, think really hard before you take this on.

Consider seeing a doctor who specializes in mold first. A crew of dedicated doctors is working to treat folks like us, and some people get good results following their treatments while doing more moderate levels of avoidance. The Shoemaker Protocol is great for some of us, and Shoemaker's panel of laboratory tests, which is generally covered by insurance, can be an excellent place to start in figuring out if mold is part of the picture for you. And of course, I'm assuming you've been getting decent medical care overall, at a minimum to make sure you're not dealing with some different disease entirely.

I'd also recommend doing a bunch of reading. ParadigmChange.me is a pretty incredible resource, and they offer the book A Beginner's Guide to Mold Avoidance for free if you sign up for their newsletter. Sara Riley Mattson wrote two wonderful books, Camp Like A Girl and Migraine: Finding My Own Way Out, which offer a lot of information about mold illness and mold sabbaticals.

One of the key considerations is what you'll do if you can't live in your home after the mold sabbatical. Your own home may well make you far, far sicker after the sabbatical than before, so don't go until you have at least a vague plan about what you'll do next.

2. If you do decide to do a mold sabbatical, get help

You are making an enormous investment in trying this, and you want to do so as wisely as possible. You’re going to have to make a thousand decisions along the way, and if you choose wrong, you may not get any useful information from your experiment at all. The people who know most about how to make those decisions are those who have been successful with extreme mold avoidance — so learn from them.

There is an ever-changing ecosystem of Facebook groups focusing on extreme mold avoidance, but right now, I’d point you to Mold and Chemical Sensitivity Lifestyle and Mold Avoiders on the Road to Recovery Camping and RVing.

I wrote a piece for Slate with concrete advice about navigating patient communities, so I’d suggest you read that first. There is an enormous amount of experience and wisdom in these groups, but you also have to take the things you read in them with a big ol' dose of salt. The experiences of people with this illness vary so enormously, and we each react to different things. It’s so, so easy to overgeneralize from one person’s experience. And if you assume you'll react to everything that anyone else has reacted to — well, you'll be left convinced that nowhere on earth will be safe for you. Reach out to the people who seem like-minded and have dealt with similar issues, and ignore the folks who make you uneasy.

And if you find yourself getting bummed out or frightened or overwhelmed, then stop. Step away from the computer, take a deep breath, get some fresh air.

Sometimes, there are successful extreme mold avoiders who work as paid health coaches. Unfortunately, right at the moment, I don't have anyone to recommend, but it might be worth asking around on those groups. If you can find a good coach, you'll save yourself a lot of work and a lot of mistakes. Just make sure it's someone you have confidence in and who has gotten good results for themselves and others.

3. Consider brain retraining First

One of the awful parts of extreme mold avoidance is that pretty much everyone who does it goes through a period of hypersensitivity, where unbelievably small quantities of mold cause devastating impacts. That’s partly valuable – it shows that mold is indeed contributing to your health problems, and it teaches you when you need to get the hell out of a building. But it also can be devastatingly difficult to deal with.

Different people have different ideas about what’s going on with hypersensitivity. Part of it seems to be related to the process of detox – our bodies absorb mycotoxins and other baddies in our tissues, and when we get out of a toxic environment, all that stuff comes oozing out of our bodies. When that load goes down sufficiently, our resiliency goes up.

But part of it also seems to be related to our brains. Extreme mold avoidance trains our brains to react: We learn to tune into tiny sensations indicating exposure, we recognize that that means we need to get the hell out, and then we go through these elaborate rituals of decontamination, etc. Each time we do that, it’s like we’re digging a groove in our brains, reinforcing a neural pathway of reactivity. It's a different thing from conscious anxiety, so it can be an issue even if you're the most chill of humans.

In Through the Shadowlands, I describe how I developed my own methods of un-digging that groove. I worked on that after I’d been avoiding mold for quite some time. But some patients who have moved to reasonably non-moldy houses have had enormous improvements from this approach alone, without having to go through the whole huge rigamarole of extreme mold avoidance. And it's relatively inexpensive and low-risk, so it may be worth trying first.

There are formal programs that have been developed for this that have been very useful for some patients. The two most well-known are the Gupta Programme and the Dynamic Neural Retraining System. There's also a new one called CFS Unravelled. All are video programs that cost a few hundred bucks and come with a money-back guarantee.

I recommend looking into these programs, but with some huge caveats. For one thing, they all oversell themselves hugely, presenting this one aspect of the illness as the central problem. There's lots of evidence that's simply not true. They also way oversell their own effectiveness. Gupta touts a study he commissioned to claim that 93% of patients improved and two-thirds recovered, but it has serious scientific problems (like no control group, small sample size, and ignoring people who didn't complete the program). This misrepresentation is bad for any treatment, but especially for one that's psychobehavioral, and even more so in an illness that has been falsely and damagingly presented as fundamentally psychological. I find this pretty much unforgivable.

In addition, I simply personally dislike the approach they take. They all emphasize positive thinking, and I rather like negative thinking, myself. It's not just that I like it, I think it's powerful and important. I try to embrace the full range of my thoughts and feelings, rather than rejecting some as "negative" or "unhelpful." Anger, for example, can be a powerful forward force. I'm not interested in diffusing it in order to reach a state of peace and equanimity as fast as possible. I want to listen to it, embrace it, tap its power, only let it go when I've gotten everything it has to offer.

Still, I used these programs as a spur for my own thinking, and I customized their ideas to fit my own personality and ways of thinking about my illness. The particular techniques I created for myself are only directly applicable once you've started avoidance, but with some thought, you might well be able to develop an approach that will work even before you've learned to recognize symptoms of exposure. The place I’d recommend starting with this (other than reading my book!) is to read Norman Doidge’s The Brain That Changes Itself. It’s very inspiring and will probably get your thoughts moving.

But also, I know enough people who have benefited from these programs directly that I recommend checking them out, in spite of all my reservations. It's a whole lot easier to follow someone else's program than to create your own, so if you resonate with one of these programs and feel it would be useful to you, then try it. It may work great for you, or you may pick up specific techniques that you find valuable while rejecting whatever bugs you.

On the other side, if you hate the whole idea of brain retraining, then ignore this! Mold avoidance will help you without brain retraining too.

If brain retraining doesn't bring you dramatic results on its own, it makes sense to set it aside during a mold sabbatical and while you're learning how to do avoidance. After all, during that period, you're trying to learn to detect the stuff you really need to get away from. You need your body to react. You can give brain retraining a try again later, when you know your level of exposure is low and you need your reactions to be softer.

4. Trust your intuition

The truth is that I have no idea if a mold sabbatical is a good idea for you, and really, nobody else knows either. Somehow, you're going to have to make a decision in the context of very limited information. In my experience, doing that well requires relying on intuition.

And that's where I hope Through the Shadowlands can provide direct guidance. While I didn't write the book to evangelize for extreme mold avoidance, I did want to evangelize for combining scientific skepticism with faith in intuition and a determination to turn this crappy experience of being sick into something meaningful.

So as you consider embarking on a mold sabbatical, start by getting really grounded in yourself. Do whatever works for you to feel in touch with your intuition. As you learn more and plan your trip, keep coming back to that calm, grounded place and make sure that exploring extreme mold avoidance feels right and whole to you. If it starts making you crazy, take a big step back.

And most of all, whether you choose to pursue extreme mold avoidance or not, craft the story you’re telling yourself about this experience into one that feels meaningful and powerful, one in which you’re an adventurer rather than a victim, one that you can enter whole-heartedly even if it’s not the story you’d choose for your life.

I wish you the very best of luck. Even if I don’t know you at all, I’ll be cheering you on from the sidelines.

If you’ve found this post useful, here are some steps you can take to learn more about my work and to help me out too:

1. Sign up for my email newsletter and I’ll let you know about my future writing, plus I'll send you a copy of the prologue of Through the Shadowlands.

2. Follow me on Facebook. My posts there are far more frequent than my newsletters – but be sure to get my newsletter too, because Facebook won’t show you all my posts. Subscribing to the newsletter will ensure that you’ll hear about the really important stuff.

3. Read (or listen to) Through the Shadowlands.

4. Spread the word. Please post a review on Amazon and Goodreads — having lots of five-star reviews really helps. And tell your friends, both about the book and about my work more generally.